經典演講:溫柔的創新巨人——Clayton Christensen

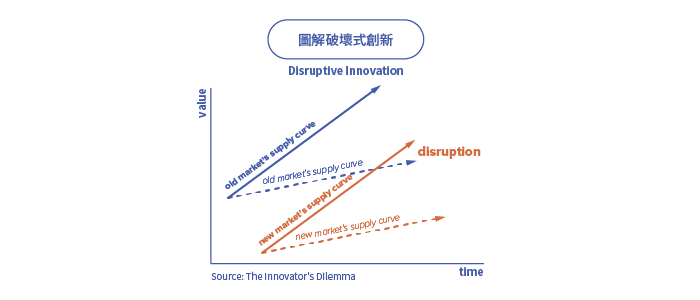

2020似乎是個不平靜的一年,新冠肺炎肆虐大大地改變全球人類的生活方式,很多計畫必須重來。這個過程加速推進「新生活方式」,許多企業也因此積極轉型,讓我們想起克萊頓克里斯的「破壞式創新」,在維持現有市場的狀況下,如何開拓新客群,帶來更便利、更便宜的商品,是目前全球企業面臨的課題。

Before you read

Clayton Christensen

克萊頓克里斯

1952—2020

WHO

哈佛大學教授、「破壞式創新」之父,創立克萊頓克里斯坦破壞式創新學院以及創投公司Rose Park Advisors。許多矽谷的科技公司、企業皆以他提出的破壞與創新架構為基調,建立組織與發展,使克萊頓克里斯被譽為當代最有影響力的創新大師,再加上203公分的身高,讓他也被稱為是「溫柔的創新巨人」“The Gentle Giant of Innovation.”

WHAT

克萊頓克里斯坦是《哈佛商業評論》的重量級作者,撰寫上百篇文章,亦有許多影響深遠的著作,包括《創新者的兩難》(The Innovator's Dilemma)、《創新者的解答》(The Innovator's Solution)《你要如何衡量你的人生?》(How Will You Measure Your Life?)等。近年在矽谷的 Napster、Amazon、Uber、Airbnb 等新創崛起,其企業理念及崛起模式都可看到破壞式創新的理論。《創新者的窘境》(The Innovator’s Dilemma)一書也被蘋果創辦人賈伯斯、Netflix 執行長 Reed Hastings等各大企業人士引用。

HIGHLIGHT

近期許多公司開始實施WFH,各大專院校也進行遠端教學。過程中,企業和學校面臨到的並非將所有業務重新來過,而是如何運用現有的素材、資源,重整出更有效率的模式、讓學生能更便利地學習等,基本上這就是「破壞式創新」的應用。既非全部「砍掉重練」,也不是打造全新的產品或服務,反而是利用原有的東西「破壞」,隨著需求轉型,變得更方便甚至更便宜,克萊頓克里斯也在本篇專訪中談到,我們如何在2020當下重新審視「破壞式創新」。

Source: The Innovator's Dilemma

*節錄自MIT Sloan Management Review特刊訪談內容

Q: Over the years, the phrase disruptive innovation has come to mean all manner of things to people. But the broad, sweeping implication that “disruptive” is synonymous with “ambitious upstart” is not correct, is it? How would you like to define disruptive innovation for the record?

多年來,「破壞式創新」一詞幾乎可以應用的人們生活中的一切,但廣泛來說,「破壞式創新」其實並不等於「有野心的新競爭者」對嗎?您會如何正式地定義破壞式創新?

A: Disruptive innovation describes a process by which a product or service powered by a technology enabler initially takes root in simple applications at the low end of a market — typically by being less expensive and more accessible — and then relentlessly moves upmarket, eventually displacing established competitors. Disruptive innovations are not breakthrough innovations or “ambitious upstarts” that dramatically alter how business is done but, rather, consist of products and services that are simple, accessible, and affordable. These products and services often appear modest at their outset but over time have the potential to transform an industry. That’s its value — not just to predict what your competitor will do but also to predict what your own company might do. It can help you avoid choosing the wrong strategy.

破壞式創新描述的是一種過程,代表一項產品或服務最初以較親民的價格及便利性打入低階市場,接著持續邁向高價市場,最終取代其他競爭者。破壞式創新並不是突破式創新或是「有野心的新競爭者」,而是更簡單、更便利且價格低的產品或服務。這些產品最初不太貴,但隨著時間展現出改變產業的潛力。這就是破壞式創新的價值,並非只是預測競爭者的下一步,也能預想出自己公司還能做到什麼。破壞式創新可以幫助你避免錯誤的策略。

Q: We’d love to hear your thoughts on the nature of disruption today versus two decades ago.

比較20年前與今日,我們想聽聽您對於破壞式創新的本質有什麼不同的想法。

A: The mechanics of disruption are the same as ever, but recent technological and business model innovations present unique opportunities and challenges for both incumbents and entrants. For example, the hotel industry hadn’t been disrupted for decades, only to be completely caught off guard by the likes of Airbnb. The internet, combined with near-ubiquitous mobile access, is continually creating very creative entry points for companies to target nonconsumers with more affordable offerings. So I don’t believe that the threat of displacement is necessarily greater, but certainly the fact that digital platforms can emerge and expand is something that I just hadn’t conceived of early in our research and deserves further study.

破壞式創新的運作方式都相同,但最近的科技與商業模式創新給已在業界的企業主以及剛開展事業的人獨特的機會與挑戰,比方說,旅館業幾十年來都沒有什麼破壞式創新,直到Airbnb突然地出現在市場上,幾乎隨處可上網的環境,持續地為公司打造出有創意的入口,鎖定以往的非客族群,提供價格更親民的選擇。我並不覺得被取代的威脅變大了,但確定的是數位平台崛起並擴張,這件事在我之前的研究中並未提到。

Q: What do you think people misunderstand about the theory of disruption?

關於破壞式創新理論,您認為大眾誤解了什麼?

A: Apart from what you’ve already mentioned, which is that disruption does not mean “breakthrough” or “new and shiny,” far too many people assume that disruption is an event. Rather, disruption is a process. It’s intertwined with the resource allocation process in the firm, in the changing needs of customers and potential customers, and in the constant evolution of technology.

除了您剛才所提到的,也就是破壞式創新並不代表「重大突破」或是「嶄新」,許多人會覺得破壞式創新是一個事件,但它其實是一個過程。破壞式創新是一家公司資源的整合,與既有顧客與潛在顧客持續改變需求,以及持續地科技進步有緊密關聯。

Q: What questions are you still eager to answer?

有什麼問題是您仍想解答的?

A: Last year I had a conversation with Marc Andreessen about The Prosperity Paradox, and we were discussing the role firms play in economic growth. Having just come back from an Airbnb board meeting, Marc described how Airbnb gives ordinary people a platform to offer their services, whether they are cooking a meal for their guests, hosting a class, or giving a tour of their hometown. These citizens would otherwise be unable to participate in the tourism industry, but because of the digital platform of Airbnb, they now can.

It occurred to me that in nearly every case, the firms we profiled to demonstrate how economies are built were those that built physical products. This meant they manufactured, distributed, sold, serviced, and designed goods for a non-consuming population, resulting in tremendous growth for their firm and their nation. But Airbnb and others like it don’t have to do any of those things, and yet they are creating opportunities all over the world. I am eager to explore further the growth potential of digital-first firms and understand what growth looks like in the years ahead.

去年我與Marc Andreessen談到 The Prosperity Paradox*,我們討論到公司在經濟成長中扮演的角色。Marc才剛開完 Airbnb的董事會,他說 Airbnb給一般人一個平台提供服務,他們為顧客煮飯、舉辦課程或是在自己的家鄉帶行程。他們原本無法踏進傳統的旅遊產業,但是數位平台Airbnb讓他們能夠做到。

這讓我想到,那些我們介紹過用以示範建立經濟的公司,都是打造實體商品。這代表他們為「非顧客」製造、分配、銷售、服務、設計商品,進而為公司及國家帶來巨大的經濟成長。 但像Airbnb一類的公司並不做這些事,卻也在全世界創造機會。我非常想進一步探索數位公司的成長潛能,並理解未來的樣貌。

參考資料:國家教育研究員雙語詞彙、學術名詞暨辭書資訊網、Cambridge Dictionary, MIT Sloan Management Review

編輯/馬婉娟

收錄於英語島 2020年6月號

訂閱雜誌