一個西方青年眼裡的侯孝賢

文/ William Blythe

侯孝賢以最新電影<<聶隱娘>>贏得坎城最佳導演獎。他說:「文化到最深層,全世界都差不多。」一個看遍他所有電影的英國年輕人,真的就在侯孝賢的眼睛裡找到莎士比亞的人性。

In my youth, I was under the false but not altogether unpleasant impression that I was different. Naturally, it was also vital that I should study something extraordinary at university. Back then, China was not the celebrity of the front pages that it is now, and Mandarin was studied mainly by eccentrics. I was, or so I thought, more than qualified for the task.

Much of the next ten years I spent studying and working abroad; first in France, then China, followed by Taiwan and Germany. Having tried for so long to be different, as a foreigner, I had to do my best to be the opposite. There was some sadness in this. My ego and a few old friends were offended. But living in different culture is, I've found, more interesting than trying to be different.

當新浪潮成為中年浪潮

The "new wave" of Taiwanese cinema swelled up roughly thirty years ago, when the films of Edward Yang, Wu Nian-zhen, and Hou Hsaio-hsien first hit the shores of film festivals across Europe and the US. Like the new wave, I am fast approaching my third decade, but I no longer feel so new. My knees ache in cold weather and I am balding rapidly. I am not, you might say, by any standard old, but the directors listed above certainly are. They are all bordering or beyond retirement age and presumably suffer from bodily ailments far greater than mine. Only Edward Yang remains eternally young. That is the privilege of dying prematurely.

電影票漲價就會有後浪嗎?

But if the new wave is now old wave, then what is to follow? I think here of the analogous Chinese expression「後浪推前浪」. There are no clear successors in sight. That is not to say that good films are no longer being made by younger Taiwanese directors. I'm a big fan of "Parking"停車 by Zhong Meng-hong(鍾孟宏). As of present, however, the younger generation has failed to wield as much clout on the international stage as their predecessors. There are reasons for this. The onslaught of Hollywood blockbusters in theatres each year makes it difficult for local movies to compete. An acclaimed Mexican director, Alejandro González Iñárritu, recently described the inane succession of superhero franchises as "cultural genocide." The damage extends as far as Taiwan. I was in favour of Minister Long Ying-tai's proposal to raise the price of cinema tickets to fund a piggy bank for Taiwanese productions. The scheme was borrowed directly from the French, who really know how to protect and promote their culture at home and abroad. A nation needs a healthy and diverse national cinema, but the truth is that good films, especially art-house films, rarely make a profit. The hits by Taiwan's most internationally acclaimed auteurs win prizes at international festivals, but at home they are often commercial failures. Edward Yang' s YiYi was not even screened in the country, while Cai Ming-liang almost has to beg his compatriots to see his films. He has yet to persuade me, at any rate.

他讓我相信古惑仔裡有天才,妓院裡有情義

But perhaps the dichotomy of art-house/commercial cinema is not the best way to understand what made the new wave such a success in the first place. During the past few weeks, Hou Hsiao-hsien has been the talk of cinema enthusiasts across the globe following the reception of his new flick"Assassin" 聶隱娘 at Cannes. Hou is often lauded as the quintessential art-house auteur, but it is easy to forget that he started out as a very commercial director. The name of his first film says it all: "Lovable You"(就是溜溜的她), a light hearted commercial rom-com that shows none of the trademark style of his later films.

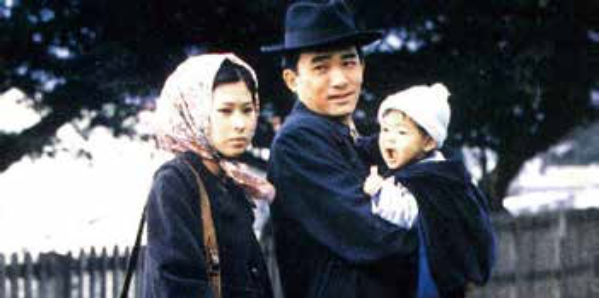

《悲情城市》,1989。圖片來源:www.worldjournal.com。

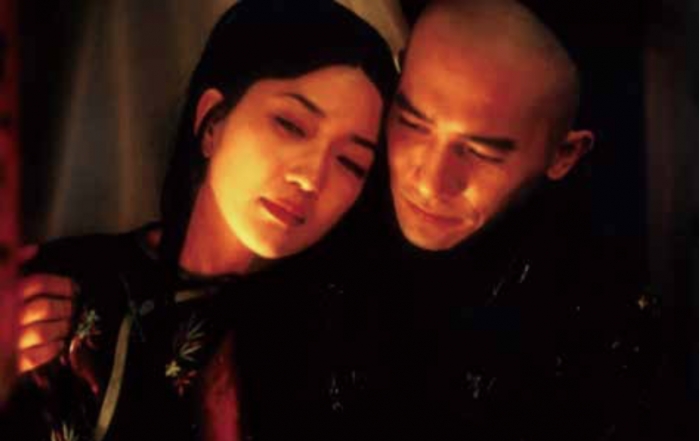

Hou's work has been subject to extensive journalistic and scholarly analysis, but for me his attraction lies in the ability to transform low life into high art. His most memorable characters all indulge in aberrant behavior. Prostitution is a common theme, featuring in"The Puppet Master", "A Time to Live and a Time to Die" and, most poetically of all, "Flowers of Shanghai." Violence and political corruption are also recurring concerns, best examined in A City of Sadness. But Hou's aim is never to condemn or to moralize, only to observe. He shows men and women as they are: imperfect but often aspiring, aggressive but often tender. His sympathy for the characters is expressed by the distant, lingering shots, in which the drama unfolds almost imperceptibly, like a flower under the morning sun. Hou's style is the absence of style – the confidence in his viewer's ability to do the seeing, without the cues of cuts and pans. We find that there is genius in hooligans and virtue in brothels.

《海上花》,1998年上映。圖片來源:YouTube。

轉動每一部電影的是同一個引擎,叫做"人性

"The French have not only bestowed honours and prizes on Hou - they've also made an excellent documentary about him."A Portrait of Hou Hao-hsien," directed by Oliver Assayas, shows the man behind the masterpieces. In the film, the master leads us around the old haunts of his hometown in southern Taiwan. An energetic child, Hou was a common contender in neighbourhood brawls. Even today, he expresses an interest in the mafia, claiming that he slightly regrets not becoming a "boss." This unfilled ambition, though strange, is revealing. It forms the connection to his subject matter. While versing himself in street life, however, Hou was also an avid reader. Literature was to play an important role in the development of his cinematic style, particularly following his collaboration with the screen-writer Zhu Tian-wen朱天文 . It was Zhu that put him onto the oeuvre of Shen Cong-wen, whose detached treatment of rural China finds echoes in his work. From his earliest film to his latest, Hou has gone through many phases of development, but behind it all there is one engine: personality. Hou has an omnivorous appetite for life and the sensitivity to observe and document it. This is a rarer gift than you might think. Saul Bellow had it. Shakespeare had it. Perhaps the reason that there has been no successor to the "new wave" is that true personalities don't come round every decade. ■

本文收錄於英語島English Island 2015年7月號

訂閱雜誌

| 加入Line好友 |  |

-- 作者:William Blythe

-- 作者:William BlytheWhen younger, I was under the false but not altogether unpleasant impression that I was different. Naturally, it was also vital that I should study something extraordinary at university. Back then, China was not the celebrity of the front pages that it is now, and Mandarin was studied mainly by eccentrics. I was, or so I thought, more than qualified for the task.

Much of the next ten years I spent studying and working abroad; first in France, then China, followed by Taiwan and Germany. Having tried for so long to be different, as a foreigner, I had to do my best to be the opposite. There was some sadness in this. My ego and a few old friends were offended. But living in different culture is, I've found, more interesting than trying to be different.

擔心生理健康,心理卻出問題?

擔心生理健康,心理卻出問題?