TANGO IN BERLIN

photo credit:flickr

photo credit:flickr

歐洲探戈第一大城

I have always imagined male tango dancers to be tall, athletic and baring abundant bouquets of chest hair. Their female counterparts I envisaged to be trim and corseted to an ideal protrusion of bosom. Accompanying my brother and his girlfriend to a Milonga this month, however, I found that none of these assumptions held true. Ninety five percent of those present were drawing a pension. The pairs were revolving around the hall in what I can only describe as a cross between spinning teacups and bumper cars.

Arriving late, I was greeted by a track-suited lady wearing the kind of ballroom smile that resists removal.

“Are you here for the class?”

The brace of simulated delight muffled her enunciation.

"We're short one man. Gertrude's partner is sick."

She pointed to a hunched septuagenarian dithering on the circumference of the floor. Her eyes were trained hypnotically on the ceiling lights, to which she addressed an inaudible but lengthy incantation.

“Could you step in?”

The smile widened.

“Alright,” I agreed, trying to sound enthusiastic.

“Great.”

She sidled back into the swarm of fragile but no doubt heavily insured athletes. I strode over to Gertrude, who was revolving on the spot at the opposite end of the hall.

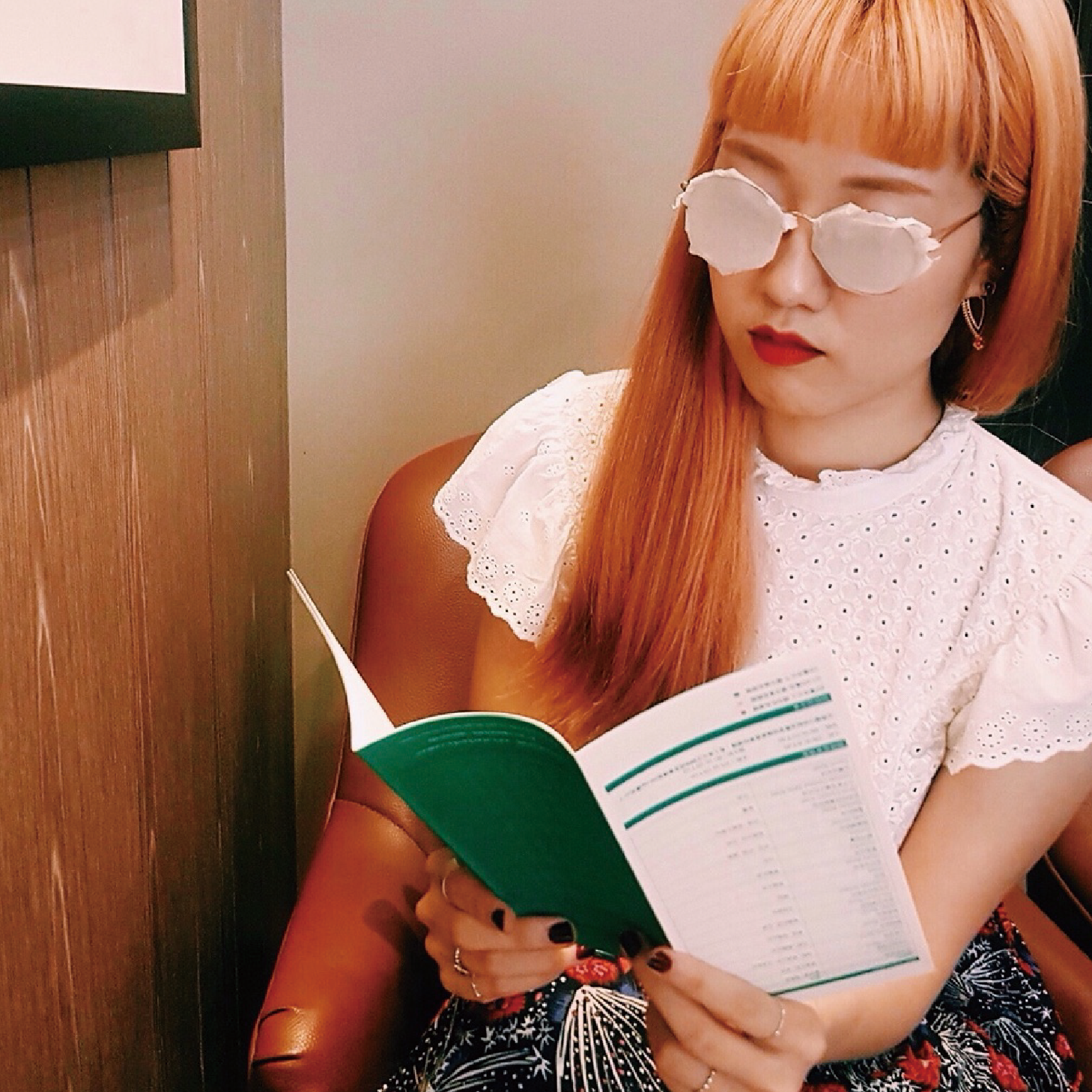

真抱歉,不是所有舞者都擁有魔鬼般的好身材

“May I have the pleasure of this dance?”

Gertrude looked at me in a transport of distress, though she may simply have been dizzy.

“You're not Humboldt.”

“Is Humboldt your usual partner?”

She inspected my face with watery eyes.

“You're not Humboldt.”

“Humboldt is sick. I'm standing in for him. Shall we?”

I extended a hand. She considered it as you would an object of minor offense, such as an unwashed dish or a dirty sock. The hand persisted. She took it.

“This is my first Tango class,” I said trying to sound jolly, “so you'll have to tell me what to do.”

My partner, however, had become distracted by the ceiling lights, while humming a tune that clashed powerfully with the melodic broadcast. I was wondering whether she was in fact deaf when the instructor descended upon the centre of the hall, accompanied by a man of obscene height and preternatural baldness. She clapped her hands, killing the music and bringing the feeble merry-go-round to a halt.

身手靈巧、記憶力好,學探戈還 要臉皮夠厚地反覆和別人打交道

“Everybody, I'd like you to meet my partner Franz.”

Franz beamed. He too wore the irremovable ballroom smile.

“Franz and I are going to show you a few simple steps that you can all try out together.”

Without further ado, she sprang into the giant's arms and froze there, as if posing for a portrait. After what felt like a perverse duration she barked “music!” Her leg slipped between his legs. His left arm went under her right arm. From within a thicket of strumming guitars, a violin careened into melody. Franz took this as his cue to release the instructor, sending her hurtling around his midriff, twirling over a buttressed leg and back into the harbour of his arms. The music stopped.

“Now, did everyone get that?” the instructor asked, panting and extricating herself from Franz's titanic grip. There was a general murmur of affirmation. I scanned the room in disbelief. Members of the retirement troupe were stretching, as if in preparation for a similar feat. I raised my hand.

“Yes?”

“Could you repeat that slowly please?”

“Alright, but just once. Now watch carefully.”

Without the music, they entwined again, counting unhelpfully in Spanish. What had before seemed like a spontaneous flurry of flight was now revealed to be a complex succession of steps, requiring all the key competencies of a professional athlete.

“Got it?”

The myopic eyes of the crowd were trained upon me. I looked to my brother for support. He held out his hands and shrugged.

“I think so.”

“Good. Give it a try.”

I turned back to Gertrude.

“Shall we just try a few simple steps,” I suggested hopefully. “Backwards and forwards. That sort of thing.”

“You're not Humboldt.”

“Yes I am. Come on, let's get moving here.”

I took her by hand and shrunken shoulder and gently willed her into motion. She didn’ t put up any resistance, nor did she give any

physical feedback. The result was blandly pedestrian; it felt as if I were pushing a shopping trolley down the dry food isle at the supermarket.

“Shall we try a spin?”

Gertrude had begun humming again.

“I said shall we try a spin?”

For all my efforts, I was unable to expand our repertoire beyond the trolley trundle. When the instructor at last clapped her hands, I experienced near bladder-loosening relief.

“Excellent! Excellent! But girls, your feet must leave the ground. It's a dance not a shuffle. And boys, your partners aren't walking sticks. Lead don't lean. Now the girls are going to move one partner to their right. Go, go.”

Gertrude drifted up the daisy chain of wilted dancers into the arms of a man who had preserved the vanity, if not the beauty, of youth. His tan was authentic. His hair was not. I was curious to hear whether she would accuse the superannuated beau of being other than the notorious Humboldt, but something tugged at my sleeve, distracting my attention.

抱緊我,再緊一點,再緊一點

“Put your arms around me.”

The voice was obscured by a riot of hair. It is often the smallest of cottages that are the most comprehensively thatched. This woman was barely five foot tall.

“Pardon?”

“Put your arms around me.”

I thought it best not to disobey.

“Like this?”

“No, closer.”

“Close enough?”

“Closer, closer. That's it.”

The small lady's head was plastered to my chest. She locked her short arms around my back, severely constricting my airways. The music began.

你先生為什麼要這樣看著我?

She mowed me back towards a pillar, swung me round with the courtesy commonly paid to industrial machinery, mowing me on again. Couples spun out of our way like the runners at Pamplona. I looked around for help. My brother and his conjoint were blocked in congestion at the opposite end of the hall. On this bleak landscape, I noticed a duo pedaling against the current towards us.

Perhaps, I thought desperately, they were coming to my aid. As they backed into line, however, I remarked that the man was looking at me with less than fraternal affection. From the intensity of his stare, you might have been forgiven for thinking that he had a minor bone to pick with yours truly. “Do you know that man?” I whispered to my diminutive partner.

She threw him a cursive look.

“That's my husband.”

It was hard to tell whether he was massaging his thick neck or shadowing the act of strangulation.

“Why, if I may ask, is he looking at me like that?”

She laughed. Hoping to appease her vice like grip, I too ventured mirthful noises, which emerged as stifled coughs. The husband's frown deepened.

“He's just jealous, that's all,” she said, resuming her austere tone. She addressed him savagely in a Slavic tongue. The V of his brow inverted, as anger switched to fear. Meek as a lamb, he directed his partner off into the crowd. I wasn't sure what was more terrifying, the prospect of being pummeled by the ogre for making advances on his wife, or finding myself in the arms of a lady who was able to rule him so ruthlessly.

“Hold me closer.”

“…”

“Closer. Yes that's it. I like that.”■

本文收錄於英語島English Island 2016年2月號

訂閱雜誌

| 加入Line好友 |  |

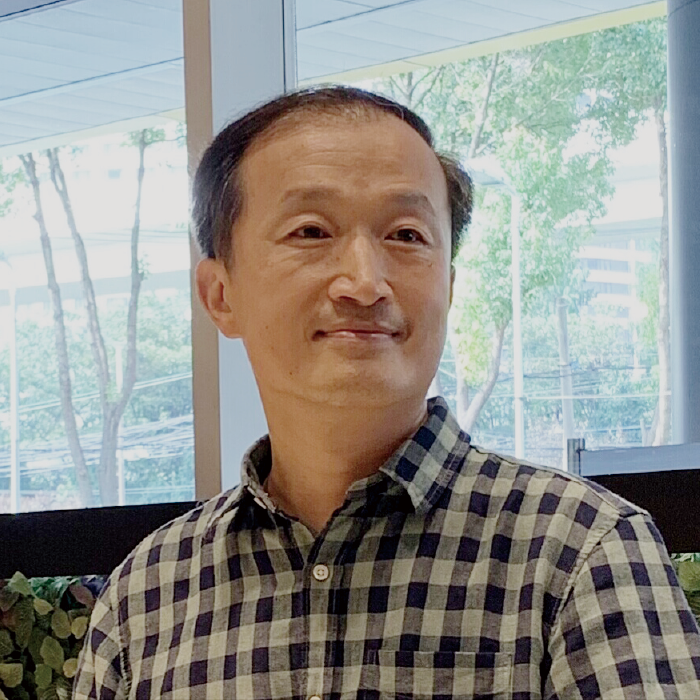

-- 作者:William Blythe

-- 作者:William BlytheWhen younger, I was under the false but not altogether unpleasant impression that I was different. Naturally, it was also vital that I should study something extraordinary at university. Back then, China was not the celebrity of the front pages that it is now, and Mandarin was studied mainly by eccentrics. I was, or so I thought, more than qualified for the task.

Much of the next ten years I spent studying and working abroad; first in France, then China, followed by Taiwan and Germany. Having tried for so long to be different, as a foreigner, I had to do my best to be the opposite. There was some sadness in this. My ego and a few old friends were offended. But living in different culture is, I've found, more interesting than trying to be different.

擔心生理健康,心理卻出問題?

擔心生理健康,心理卻出問題?