關於政治,食物不會騙你 —— Anthony Bourdain

美國知名廚師、電視節目主持人安東尼波登在2018年6月初辭世。他在節目中散發出的真摯情感令人印象深刻,驟然離世的消息也特別令人感到不捨。波登曾表示:「每道菜背後必定有一段深遠的歷史,通常是令人難過的」。他在節目中所呈現的除了跨越文化的體驗外,還總帶著對人性更高層次的關懷。透過這篇關於食物如何反映生活的訪談,我們可以一同紀念他所留給我們的精神。

Before you start

Anthony Bourdain

安東尼・波登

1956年6月25日 - 2018年6月8日

WHO

波登是美國知名廚師,22歲時進入美國烹飪學院就讀,38歲當上紐約一間法式餐廳的行政主廚。自2002年開始電視節目主持人生涯,著名節目包含《No Reservations》、《Parts Unknown》,後者在2013至2016年四度獲得艾美獎最佳知識類節目獎。

WHAT

除了烹飪外,波登也致力於寫作,1999年刊出一篇名為《Don’t Eat Before Reading This》的文章,揭露紐約餐廳人員私下的問題,此後聲名大噪。以此文延伸的第一篇書籍作品《Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly》賣出超過100萬本。

HIGHLIGHTS

波登近年最有名的一集節目,是與美國前總統歐巴馬一同在越南河內品嚐當地小吃。此次行程對維安人員而言非常突然且具有挑戰,因為他們造訪的小吃店空間相對狹小,所有的維安與劇組人員都必須待在店外。然而,波登認為這倒是一個很好的機會,讓整段節目的互動更真實自然。

一切從一顆生蠔開始

波登對廚藝的熱愛始於他10歲時一趟法國探親之旅,一位友善的漁夫鄰居邀他們全家到他的漁船上一日遊,在船上波登吃到生平第一顆現採的新鮮生蠔,他形容他在那一口中生蠔似乎嚐到了某種未來。雖然青少年時期的波登曾夢想成為漫畫家,但這個美好記憶從未在他心中淡化,最終使他踏上廚師之路。

早午餐是羞恥的味道

波登說他最討厭做的菜是美式早午餐,因為在他廚師生涯遭遇挫敗,無法在知名餐廳任職時,只能在職缺多的美式早午餐店中工作度日。煎歐姆蛋、法式吐司的味道,總是讓他想起那段痛苦的日子,是一個代表羞辱、不堪的味道。然而當女兒出生後,試著改變這個心態,因為當女兒帶朋友來家裡玩時,弄個早午餐吧檯總是能讓孩子們興奮不已。

訪談節錄

節錄自CBC News 2016年訪談

Q1:To what extent is food the best, or maybe least biased glimpse into how a society, a country, and economy works?

食物是不是最適合、或相對公正地窺視一個社會、國家經濟狀態的事物?能看到什麼程度?

Well, there is nothing more political. There’s nothing more revealing of the real situation on the ground whether the system works or not. I mean whatever your philosophical foundation of your personal belief system, it’s difficult to spend time in Cuba, particularly like 10 years ago, eat with ordinary people and come out of it thinking, “Wow, this system is really working out for everybody”. Who gets to eat, who doesn’t get to eat, what they are eating, I mean the food itself on the plate is usually the end result of a very long and often very painful story.

沒有任何事物比食物更具政治性了。食物能最真實的呈現一個地方的經濟系統是否有效。無論你怎麼看古巴,要在那裡生活上一陣子真的是有些痛苦的,更別說在10年前。在那裡和平民百姓一起吃飯,然後想著「哇!這種經濟模式在這裡還真的行得通」。誰有東西吃?誰沒有東西吃?人們都吃些什麼?盤中的食物通常都來自一個又長又痛故事。

There’s a lot of food preservation, there’s a lot of pickling. You know certain countries their cuisine very much reflects either a siege mentality or abundance or intermittent periods of difficulty. Also if you go in not as a journalist but just as somebody who’s asking simple questions like “What do you like to eat,” “What makes you happy,” people tend to drop their defenses and tell you extraordinary things. They’re very revealing.

每個國家都會有很多食物的保存方法、很多醃漬的食物。食物反映出了國家的不同狀態,無論是受害者的心態、食物的豐饒程度、或是常常需要共體時艱等等。 如果你不以一個記者的姿態訪問當地,而是像個路人一樣隨性問一些簡單問題,像是「你喜歡吃什麼?」「什麼東西會讓你開心?」,人們比較會卸下心防,然後非常坦白的告訴你一些很獨特的事情。

Q2:Where do you get the stuff? I mean how you get all this food tells you so much about how an economy functions?

你是怎麼找到這些能夠反映經濟的食物的?

I think maybe the strongest example snuck up on us when we were shooting in Egypt before the Arab Spring. We wanted to shoot a scene with a Ful [Ful Medames], which is an everyday sort of food which working-class [people eat in] Cairo. And our fixers and local translators suddenly were all up in arms. “No, no, no, you must not shoot this. You can’t shoot Ful.”… “It’s forbidden. We’ll kick you out” [they told us]. We ended up getting the shot anyway. There were devious strategies.

最顯著的例子就是在埃及拍攝的那集,那是在阿拉伯之春發生的前夕。我們想拍攝一個埃及傳統燉蠶豆的鏡頭,這是平民階級再日常不過的食物,但突然間我們的地陪跟翻譯跑過來阻止我們「不不不,你們不能拍這個!」「官方規定不能拍,你拍了的話他們會趕你走」,即便我們最後還是用了一些旁門左道拍到了這個鏡頭。

But what I think what they were concerned about was they understood it’s not just typical, it’s all there is to eat. The army controlled, I guess, the flour supply. There’d been bread riots. They were not so much worried about how it would look outside the country, but the show is aired within the country and I didn’t think they wanted their own people seeing it. Particularly afterward episode of the same show shot in France.

我想當局是意識到了這道菜所象徵的意義,當時似乎因為有些糧食的暴動,所以軍隊控制了麵粉的供應,那道燉肉豆就成了當地居民唯一能吃的食物。他們真正在意的不是外國的觀點,而是不希望國內其他地區的人,透過此節目看見這件事。況且在這節目的前幾集,是在法國拍攝的,那將會形成鮮明對比。

On my show I get the comments “Stick to the food, man” “We don’t want to hear politics from you. You’re a chef.” “Shut up, we don’t want your political opinion.” Okay, fair enough, but it’s difficult to not notice the elephant in the room.

“How come you only have these fish?”

“Well we can’t go any further out to sea.”

“How come you’re missing two of your limbs?” in Laos,

“When I was a little boy, I was walking around in the field and stepped on one of the 8 million tons of ordnance you guys left in my country.”

Look, those are inescapable facts. How you choose to feel about them and interpret them is up to you.

我有收到一些關於我節目的評論,像「專心討論食物吧!」「我們不想聽一個廚師談政治」「閉嘴,我們不需要你的政治意見」。好吧!我覺得這樣說還算公道。但你其實沒有辦法掩耳盜鈴。

例如問:「為什麼你只有這一點點漁獲?」,他們回答「因為我們不能再出海更遠了。」*;

在寮國問一位朋友「為什麼你失去了雙腿?」,他回答「我小時候走在路上,不小心踩到了你們留在這裡的地雷」。

這種問答都會顯露許多不可避免的事實。但你要如何感受、如何詮釋它,就取決於你自己了。

*因為以色列封鎖加薩走廊,限制巴勒斯坦漁船活動範圍不能離岸超過16公里,導致漁獲量非常有限。

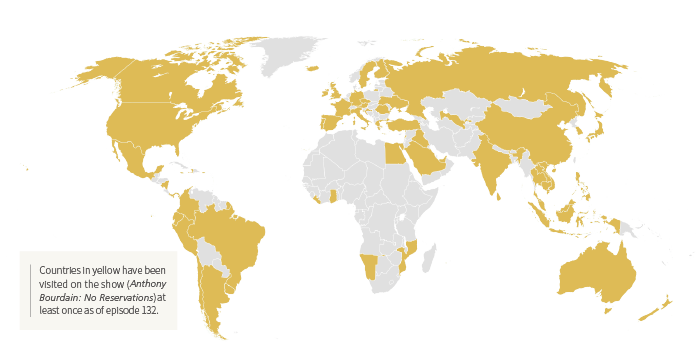

《No Reservations 波登不設限》節目造訪過的國家

本文收錄於英語島English Island 2018年7月號

| 加入Line好友 |  |

-- 作者:Speakers

-- 作者:Speakers英語島雜誌每期經精選一篇名人的經典演講,有的對歷史產生重大影響,有的改變了某些人的生命,有的讓我們看見不一樣的觀點

,皆有之成為經典的原因。

擔心生理健康,心理卻出問題?

擔心生理健康,心理卻出問題?